Early Modern Maritime Recipes collects recipes circulating before 1800 in what is now defined as Canada’s Maritime provinces (a few nineteenth-century recipes from collections begun in the eighteenth century are also included). What we now call New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island were first inhabited by the Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet), and Passamaquoddy peoples and then also by Settlers arriving from Europe and the American colonies. The recipes that survive in the region’s archives collected here in digital form are mostly in English and represent the work of printers and Settlers writing in the later decades of the eighteenth century. Though the project has also uncovered a number of recipes and medical remedies recorded in Latin, German, and French, the Anglo linguistic and cultural predominance of the archive is a result of the politics of the region (for more on this, see Historical Context).

The database includes recipes from print and manuscript sources. Recipes were printed in newspapers and almanacs in two of the three Maritime provinces. The Nova Scotia Calendar, or an Almanack was printed in Halifax with recipes, and multiple Nova Scotia newspapers circulated with recipes, as did The Royal Gazette and Miscellany of the Island of Saint John, from Charlottetown. We did not find any recipes in New Brunswick newspapers.

The manuscript sources include a few dedicated notebook recipe collections, but more commonly recipes were recorded alongside other types of texts. These include a military order book and a militia regulation book, a church register, account books, a planting journal, diaries, and letters. Sometimes multiple people have used a single notebook, and unlike with newspapers, it can be impossible to establish a precise date for many handwritten recipes. Recipes also cross from print to manuscript culture as people paste or copy printed recipes into their notebooks—and from manuscript to print--as printers purport to make available recipes they have received in letters. Many of the images are taken from microfilms because the original papers are not held in Maritime archives or are not accessible.

We have excluded recipe books printed elsewhere that were brought to the region (and no recipe books were printed here in this period).

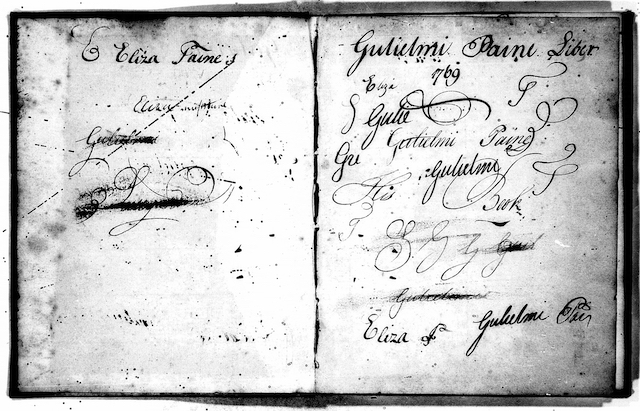

When recipes in the database are connected with individuals, they are mostly men. This gender imbalance distinguishes Maritime recipe culture from the British culture with which we are more familiar. There, women compiled many surviving manuscript recipe collections and were the authors of several popular collections that appeared in print before 1800. None of the printed recipes in our collection name a female source. In manuscript, women included a few recipes in letters: Rebecca James Almon sent an eye remedy to her aunt, and Margaret Hutchinson wrote her sister in Boston with a recipe for restoring jam. The Almon Scrapbook contains a recipe for a mutton pie from “our dear Mary Byles of Granada.” The name “Eliza Paine” is inscribed on the page opposite of a front cover for a manuscript recipe collection signed Gulielmi Paine Libre 1769,” marking it as William Paine’s book; it also belonged to Eliza, perhaps Dr. Paine’s daughter Elizabeth (Paine 24).

Compiler of a collection begun at the very end of our period, Sarah Creighton Wilkins is the only women we have found who collected and recorded a large number of recipes. We continue to search for more recipes made by, exchanged between, or belonging to women. The predominance of recipes used and circulating among men may be a distinguishing feature of the surviving recipe archive.

Attributing recipe authorship is in any case uniquely challenging. Recipes can have originators, who create the recipe, compilers who collect them, and contributors whose recipes have been shared. Recipes can be passed down from earlier generations, with later members of families adding to and altering earlier collections and recipes themselves. Michelle DiMeo has written about how participants in early modern recipe culture did not have a shared ideology of authorship, with some regarding the donor of the recipe as its author—an approach that requires further thinking about how authority for recipes is shaped within social networks (38-43). Among the recipes included in the EMMR database, there is in many cases little or no evidence to help identify a given recipe’s provenance given that written recipes can be gleaned by word of mouth, or simply copied from other sources, both handwritten and printed.

When there are names associated with a recipe, the EMMR protocol is to identify those who have recorded a given item as “Compiler” and reserve the category of “Author” for those where the person who created the technique is clearly identified within the recipe itself. Given that we most often don’t know if a named source also received the recipe from elsewhere, we admit that our chosen practice isn’t problem free; we also recognize that our protocol for naming “Compiler” and “Author” may sometimes deny authorial credit to those who may have devised and not merely recorded the recipes we share. Recipes are, in any case, most often the product of many practitioners. It is important to remember, too that written recipes are not the entirety of a recipe culture, as people persist in making and doing apart from the written word (there is little need to write down the recipe one uses every day).

We have defined recipe broadly as a text that includes ingredients and offers practical instructions on how to do something with those materials. Recipes can also commonly include comments on application—what the recipe is for—and efficacy—how good it is at doing that thing. While today recipes are mostly associated with cookery, in the eighteenth century and before, the form was used in a variety of fields of knowledge. At the time of writing, there are more recipes for medicines in our database than for food. The database also includes instructions for products used in the agriculture. These texts, too, define themselves as recipes. “Recipe for preventing the Fly in Turnips” provides instructions for making a pesticide, for example. A printer used the word “Recipes” to precede a set of instructions to “Multiply the increase of Corn,” “prevent the Smut in Wheat” and to prepare seed for planting. The recipes in this database include instructions—conveyed with varying levels of detail—for a wide array of processes. We have included recipe texts that have been placed inside other types of texts, the travel narrative that pauses to explain a process, the letter that conveys information on how to heal a wife, and the herbal entry that describes how to use a plant alongside its geographical location and other qualities.

As the site of the first colonies in the territories now known as Canada, a colony beset with intra-European conflict, as well as displacement of Indigenous peoples and colonial wars, Maritime recipes provide valuable insights into the early modern Atlantic world.

Works Cited

Dimeo, Michelle. “Authorship and Medical Networks: Reading Attributions in Early Modern Manuscript Recipe Book.” Reading and Writing Recipe Books, 1550-1800, edited by Michelle DiMeo and Sara Pennell, Manchester UP, 2013, pp. 25-46.

Paine, Nathaniel. Genealogical Notes on the Paine Family of Worcester, Mass, privately printed, 1878.